Flossenbürg concentration camp

| Flossenbürg | |

|---|---|

| Nazi concentration camp | |

| |

| Location | Flossenbürg, Bavaria, Germany |

| Operated by | Nazi Germany |

| Commandant | List

|

| Companies involved | German Earth and Stone Works, Messerschmitt AG |

| Operational | 3 May 1938 – 23 April 1945 |

| Inmates | Political prisoners, Jews, criminals, antisocials |

| Number of inmates | 89,974 |

| Killed | c. 30,000 |

| Liberated by | United States Army |

| Website | www |

Flossenbürg was a Nazi concentration camp built in May 1938 by the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office. Unlike other concentration camps, it was located in a remote area, in the Fichtel Mountains of Bavaria, adjacent to the town of Flossenbürg and near the German border with Czechoslovakia. The camp's initial purpose was to exploit the forced labor of prisoners for the production of granite for Nazi architecture. In 1943, the bulk of prisoners switched to producing Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter planes and other armaments for Germany's war effort. Although originally intended for "criminal" and "asocial" prisoners, after Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union, the camp's numbers swelled with political prisoners from outside Germany. It also developed an extensive subcamp system that eventually outgrew the main camp.

Before it was liberated by the United States Army in April 1945, 89,964 to 100,000 prisoners passed through Flossenbürg and its subcamps. Around 30,000 died from malnutrition, overwork, executions, or during the death marches. Some of those responsible for these deaths, including administrators, guards, and others, were tried and convicted in the Flossenbürg trial. The camp was repurposed for other uses before the opening of a memorial and museum in 2007.

Background

[edit]

During the first half of 1938, the Nazi concentration camp population expanded threefold due to increased arrests by the Schutzstaffel (SS) of individuals deemed undesirable, especially "asocial"[a] and "criminal"[b] prisoners, to create a slave labor force. SS leader Heinrich Himmler ordered the founding of new concentration camps to expand the SS economic empire.[4][5] The SS intended to exploit the slave labor of prisoners to quarry granite, which was in high demand for monumental building projects in the Nazi style.[6][7] This would also profit the SS-owned and -operated company German Earth and Stone Works (DEST),[8][9] which had been founded in April.[10][11]

During the second half of March 1938, a high-ranking SS commission led by Oswald Pohl and Theodor Eicke toured southern Germany, searching for a site for a new camp that would meet the SS' specifications.[12] On 24 March 1938, they chose a site near the small town of Flossenbürg, in the Upper Palatinate, for the establishment of a concentration camp[5] due to the quarries of blue-gray granite located nearby.[12] Unlike all other Nazi concentration camps to date, which were near rail junctions and population centers, the camp was to be located in the remote Upper Palatine Forest near Flossenbürg Castle, formerly owned by Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa.[8]

Flossenbürg was a poor rural area, with about 1,200 inhabitants who mostly worked on the quarries, which had existed since the 19th century. The local economy, especially the stone industry, was negatively impacted by the new border with Czechoslovakia after the Treaty of Versailles and the 1930s economic slump. Adolf Hitler's rise to power increased the demand for granite, earning the Nazi Party local support.[13][14] The construction of the camp was funded by a contract with Albert Speer's ministry for the reconstruction of Berlin;[15] it was the first occasion that economic considerations had determined the site of a camp.[16]

Establishment

[edit]

The order for the construction of eight barracks at Flossenbürg went through on 31 March,[18] SS guards arrived in April,[19] and on 3 May 1938, a transport of 100 prisoners arrived from Dachau, establishing the camp.[5] More prisoners arrived from Dachau on 9 and 16 May;[20] Himmler visited the camp on 16 May with Pohl, indicating that the SS considered it an important project.[16] The SS attempted to segregate prisoners incarcerated for criminal offences at Flossenbürg because forced labor in the quarries was considered a particularly harsh punishment.[21] Most of the prisoners at Flossenbürg were classified as criminal, with some "asocial" and a few homosexual prisoners;[c] the criminals quickly took over the prisoner functionary positions.[5]

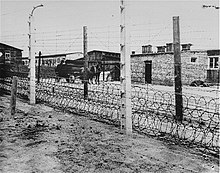

The new prisoners had to construct the camp themselves, beginning with the barbed wire fence; this was initially the main use of forced labor.[9] While performing this heavy and dangerous work, the prisoners lived in makeshift structures. Simultaneously, hundreds of prisoners had to work in the quarries.[23] The camp's population had increased to 1,500 following arrivals from Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald.[5] In January 1939, the first commandant, Jakob Weiseborn, unexpectedly died.[24][25] He was replaced by a former SS officer at Dachau, Karl Künstler, who presided over an era in which the camp became an economically productive center for granite quarrying,[25] and increasingly deadly for its prisoners.[24] With the first barracks complete, in 1939 work began on an internal jail, guard towers, a washing facility, and a sewer system.[9] In April 1939, the economic productivity of the camp led to Pohl ordering the camp to be expanded to fit 3,000 prisoners. To build additional barracks, terraces had to be cut into the hillsides, an arduous task that led to many injuries.[26]

Fifty-five prisoners died before the outbreak of World War II in September 1939.[27] During mid-1939, Nazi authorities planned to invade Poland. It was decided to stage false flag attacks in order to justify a German declaration of war. Several prisoners from Flossenbürg and other concentration camps were secretly transferred to a Gestapo prison in Breslau, poisoned, and dressed in Polish uniforms. On 31 August 1939, the bodies were dumped at a border post in Hochlinden where they were shot and hacked; photographs were taken as "proof" of a Polish attack on Germany.[28]

Expansion

[edit]

In September 1939, the SS transferred 1,000 political prisoners to Flossenbürg from Dachau in order to clear the latter camp to train the first regiment of the Waffen-SS. These prisoners, who were the first political prisoners at Flossenbürg, were moved back to Dachau in March 1940.[29][30] The first foreign prisoners were transferred to the camp by the Gestapo in April, including Czech student protestors and Polish resistance members. The vast majority of the new foreign prisoners were incarcerated due to their opposition to the Nazi regime; a few of them were Jews. Most of the Jewish political prisoners were executed or died shortly after arriving from mistreatment.[31][32] The last twelve surviving Jews were deported to Auschwitz on 19 October 1942, pursuant to Himmler's order to make the Reich Judenrein.[9][32]

The number of Polish prisoners increased sharply in 1941; on 23 January, 600 arrived from Auschwitz.[33] In mid-October 1941, 1,700[34] to 2,000[9][32] Soviet prisoners of war arrived at Flossenbürg as part of a massive transfer of Soviet prisoners to the SS camp system. In poor condition due to their previous mistreatment, they spent several months recovering before they were deemed fit to work. They were accommodated in a special, cordoned-off area.[35]

By February 1943, Flossenbürg had 4,004 prisoners, not including the Soviet prisoners of war.[32] From April 1943, the commandant was Max Koegel, described by American historian Todd Huebner as "a vicious martinet" who lacked the ability to manage the camp during its rapid expansion.[36] Continuing influxes of political prisoners from occupied countries caused Germans to become a minority that same year.[9] During 1944, Flossenbürg's population expanded almost eightfold, from 4,869 to 40,437,[37] due to a high influx of mainly non-German prisoners.[9] This was part of an expansion that applied over the entire Nazi concentration camp system.[38]

By the end of 1943, the number of guards had increased to about 450, including 140 Ukrainian auxiliaries. As with other concentration camps, guards initially consisted of SS men from Germany and Austria, whose ranks were augmented with Volksdeutsche recruits after 1942. The number of guards increased sixfold during 1944 and reached 4,500 by the time the camp was evacuated. Due to manpower shortages, fit young guards were called up for front-line service and many older men, members of the Wehrmacht and five hundred SS women were recruited into the guard force at Flossenbürg.[36]

Subcamps

[edit]

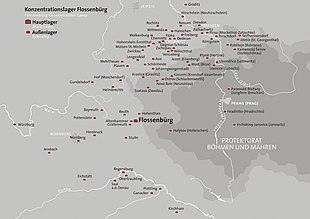

The expansion of the camp led to the establishment of subcamps, the first of which was established at Stulln in February 1942 to provide forced labor to a mining company. Many of them were located in the Sudetenland or across the border in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Initially, the subcamps were not involved in armaments production, which changed in the second half of 1944 due to a large influx of available prisoners and the activities of the Jägerstab, which sought to increase German aircraft production.[39] The Jägerstab's dispersal of aircraft production spurred the expansion of the subcamp system in 1944[40] and resulted in the establishment of the two largest of the subcamps, at Hersbruck and Leitmeritz.[39] In the second half of 1944, 45 new camps were created, compared to three camps in the previous six months. The staffing of these new camps was increasingly filled by Luftwaffe soldiers, Volksdeutsche SS men (ethnic Germans from outside the Reich), and SS women, for the subcamps containing female prisoners.[41] By April 1945, 80% of the prisoners were at the subcamps.[42]

Forced labor

[edit]Quarries

[edit]

Three quarries were operational by the end of 1938, and a fourth opened in April 1941.[43][44] All four quarries were located near the main camp, and the total planned output was 12,000 cubic metres (420,000 cu ft) annually. The stone was average quality blue-gray and yellow-gray granite, 90% of which was suitable for architectural purposes.[44] Production gradually increased during 1940, but remained constant in 1941.[45] Initially all work was done by manual labor;[46] prisoners worked alongside civilian laborers and performed the most arduous and dangerous tasks. Accidents led to many deaths.[47] Beginning in 1940 and 1941, machines were introduced to increase efficiency.[46] In mid-1939, the quarries became the main use of labor in the camp and the following year they consumed half of the total labor, which was valued at 367,000 Reichsmarks.[48]

From November 1940, some prisoners were trained as stonemasons in a specialized workshop; their numbers reached 1,200 by December 1942.[49][50] The prisoners were instructed by civilian experts in a ten-week course covering both practical and theoretical topics but watched carefully by kapos. Those who failed to advance were sent to work in the quarries, while those whose productivity improved were given cigarettes and extra food. The stone that they cut was used for construction of the camp, the Autobahn, and various SS military projects,[51] but later on it was destined for the monumental German Stadium project and the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg.[52]

Of the five prewar concentration camps where economic industries were prominent, Flossenbürg was the one that was most significant and consistent in producing income for DEST. For example, it produced 2,898 cubic metres (102,300 cu ft) of stone in 1939, almost three-quarters of the total production that year.[53] The largest buyer of Flossenbürg granite was Albert Speer's office for the reconstruction of Berlin.[8] Within this project the largest and most significant orders were for Wilhelm Kreis' Soldiers' Hall (Soldatenhalle) project, beginning in 1940. Increasing amounts of stone were used for road building; 15% in 1939 but 60% the next year.[54]

The first quarry shut down in May 1943 and its workers were reassigned to arms production,[53] but half of the prisoner labor was still going to the quarries.[55] Although civilian production was being scaled back in order to reorient the economy to total war, DEST managed to secure permission to keep many of its quarries open into 1944.[56] At Flossenbürg, the company maintained strong control over the economic enterprises of the camp, despite the fact that this aspect was supposed to be under the control of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-WHVA).[25] In early 1944, 1,000 prisoners were still employed in the quarries.[56]

Aircraft and armaments

[edit]

During 1942, the focus of the SS shifted towards war production, leading to negotiations with arms manufacturers to license their products to DEST.[57] Messerschmitt AG was one of the most important armaments companies that demonstrated interest in acquiring the slave labor of concentration camp prisoners, opening negotiations with DEST via Rüstungskommando Regensburg by the end of 1942 to produce parts for the Messerschmitt Bf 109 aircraft at Flossenbürg. Under the terms of the deal, Messerschmitt would provide skilled technicians, raw materials, and tools, paying DEST 3 Reichsmarks per day for a skilled laborer and 1.5 Reichsmarks per day for an unskilled prisoner. Thus, Messerschmitt could increase its profit margin by reducing labor costs, while DEST could reduce its administrative costs by acting as a manpower agency. In mid-January 1943, DEST accepted the offer;[58] production started in early February.[58][55]

According to Yad Vashem historian Daniel Uziel, the conversion of Flossenbürg to armaments production was especially significant because it had been the most profitable DEST enterprise. The number of prisoners working for Messerschmitt increased greatly after the bombing of Messerschmitt's Regensburg plant on 17 August 1943.[59] That month, 800 prisoners worked for Messerschmitt; a year later, 5,700 prisoners were employed in armaments production.[55] Erla Maschinenwerk, a subcontractor of Messerschmitt, established Flossenbürg subcamps to support its production: a subcamp at Johanngeorgenstadt, established in December 1943, to produce tailplanes for the Bf 109, and another subcamp at Mülsen-St. Micheln which produced aircraft wings, in January 1944.[40] Despite strict regulations forbidding contact, the German civilian workers came into contact with prisoners and some helped by providing extra food or other assistance.[60]

The Flossenbürg camp system had become a key supplier of Bf 109 parts by February 1944, when Messerschmitt's Regensburg plant was bombed again during "Big Week". Seven hundred Soviet prisoners who had been working at the Regensburg factory were transferred to Flossenbürg to continue working on Bf 109 production. Increased production at Flossenbürg was essential to restoring production in the aftermath of the attack. Aircraft manufacturer Arado eventually became one of the primary users of slave labor at the subcamps for the Arado Ar 234 jet bomber project, at Freiberg among other locations.[40] Other prisoners in the subcamps were forced to work on synthetic oil production or repairing railways.[41] Before the end of the war, about 18,000 prisoners at Flossenbürg and its subcamps were working on aviation-related projects.[61]

Conditions

[edit]

Ten percent of the deaths at Flossenbürg occurred before 1943. The quarries caused the death rate to be higher at Flossenbürg than at camps with less physically demanding industries, such as brickworks; the switch to armaments production in 1943 led to a decrease in the death rate.[62] Prisoners also suffered from a shortage of fresh water, due to the elevation, and unusually cold and wet weather; their clothing was not adequate for these conditions. The main camp, situated in a narrow valley, had little room for expansion. Originally constructed for only 1,500 prisoners, the population of the main camp increased to between 10,000[9] and 11,000[32] before it was evacuated in April 1945. In order to increase productivity, the prisoners were forced to sleep and work in shifts. This also helped alleviate the chronic overcrowding in the barracks.[9]

The prisoner functionaries at Flossenbürg were unusually brutal and corrupt because the positions had been taken by criminal prisoners even though overall only about 5% of prisoners had been classified as criminal. The final camp elder, Anton Uhl, was beaten to death by prisoners after liberation. Many of the criminal functionaries sexually abused young male prisoners, causing the commandant to isolate teenage boys in separate barracks. The SS hierarchy was also known for corruption and brutality. Prisoners were mistreated in various ways, from being beaten or doused with cold water to being shot by guards during alleged escape attempts.[63]

The prisoners were chronically undernourished and disease was rampant.[36] Conditions differed based on a prisoner's status and race. Polish and Soviet prisoners occupied the lowest rungs on the prisoner hierarchy, being put on the most physically demanding work details and allocated less food than other prisoners.[33] There was an epidemic of dysentery in January 1940 that shut down work at the camp, and typhus epidemics in September 1944 and January 1945 claimed many lives.[36] The total number of prisoners who passed through Flossenbürg and its subcamps has been estimated at 89,964[9] or over 100,000.[64] About 30,000 of the prisoners died at Flossenbürg or during its evacuation,[9][64] the main causes of death were malnutrition and disease.[36] Between 13,000 and 15,000 prisoners died at the main camp and more than 10,000 at the satellite camps.[64] An estimated three-quarters of the deaths occurred in the nine months before liberation.[65]

Executions

[edit]

Due to increased mortality from the harsh conditions, the SS ordered the construction of an on-site crematorium, which was completed in May 1940.[66] Executions by shooting began at Flossenbürg on 6 February 1941; the first victims were Polish political prisoners. Victims were separated after the evening roll call and read their sentences. After a night in the camp jail, they were shot at the firing range adjacent to the crematorium. After a mass execution of 80 Polish prisoners on 8 September,[67] the execution method was changed to lethal injection due to complaints from local residents of blood and body parts washing up in nearby streams.[68] The primary victims were Polish political prisoners and Soviet prisoners of war.[36]

Doctors who had participated in the Aktion T4 mass killings toured several concentration camps to select ill inmates to be transported to euthanasia centers; they visited Flossenbürg in March 1942.[69] Thousands of prisoners who were worn out by forced labor were sent to death camps such as Majdanek[70] and Auschwitz. One transport from Flossenbürg to Auschwitz arrived on 5 December 1943 with more than 250 of the 948 prisoners dead. By 18 February, only 393 survived.[71] Women unable to work were often deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp.[72]

The rate of executions increased during the final months of the camp. The SS liquidated prisoners who they suspected might try to escape or organize resistance; most of the victims were Russians.[73] Some of them were high-profile prisoners who had been kept alive previously for interrogation. During the last days of the camp's existence, the SS executed thirteen Allied secret agents and seven prominent German anti-Nazis, including former Abwehr head Wilhelm Canaris and the Confessing Church theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer.[74][36] In all, the SS had executed at least 2,500 people at Flossenbürg.[75]

Final months

[edit]

A total of 12,000 prisoners in seventeen transports arrived at Flossenbürg in late 1944 and early 1945, causing the camp to fall into a state of disarray.[76] The first of these prisoners had been evacuated from Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp in summer 1944.[77] In early 1945, 2,000 prisoners were sent to Flossenbürg during the evacuation of Auschwitz concentration camp.[78] 9,500 prisoners arrived after the evacuation of Gross-Rosen; of 3,000 on one transport, only 1,000 arrived alive.[79] The influx of prisoners caused conditions to worsen and the death rate to increase dramatically: 3,370 prisoners died between mid-January and 13 April.[73]

As there was not enough space in the infirmary for all of the sick prisoners, commandant Max Koegel ordered hundreds of sick prisoners sent to Bergen-Belsen in April. In order to cope with the disorder, he founded a camp police force composed of ethnic German prisoners, mostly criminals. These prisoners mistreated non-German prisoners.[76][80] During the last months of the camp's existence, many of the prisoners were idle because no raw materials for their work had arrived.[81] Because of its location near the border of the Protectorate, Flossenbürg was the destination for evacuation transports from Buchenwald concentration camp when the Allies neared the camp in mid-April. At least 6,000 prisoners from Buchenwald[76] arrived at Flossenbürg between 16 and 20 April; many of the Jews were sent on to the Theresienstadt Ghetto while non-Jewish prisoners remained at Flossenbürg.[82] On 14 April, the population of Flossenbürg and its subcamps was 45,800, including 16,000 women.[76] The main camp's population peaked at between 10,000[9] and 11,000.[32]

Death marches

[edit]

On 14 April 1945, SS leader Heinrich Himmler ordered all of the camps to be evacuated: "Not a single prisoner must fall alive into enemy hands".[83] As soon as he received the order, Koegel sent some families of SS men away and prepared to evacuate the camp.[76] At 5 am on 16 April, the 1,700 Jewish prisoners at Flossenbürg main camp were separated from the rest and ordered to assemble. Eight SS men guarded each column of 100 prisoners. When they reached the railway station, 4 miles (6.4 km) distant, they were loaded into closed and open freight cars, 60 to 75 each.[84] The train was strafed by United States aircraft soon after setting out, causing the guards to flee temporarily. Many prisoners were injured or killed; others rummaged for food that the SS guards had left behind. After the raid, the guards returned and shot injured prisoners. The total number of deaths was several dozen, increasing in the next two days as the prisoners were not provided with food or water.[85]

The route proceeded by rail through Neunburg vorm Wald, Weiden in der Oberpfalz, Pfreimd, Nabburg, and Schwarzenfeld, where, on 19[86] or 20 April, about 750 of the Jewish prisoners were stranded after another aerial attack disabled the locomotive. The SS murdered any prisoners who were unable to continue the march on foot. After the liberation, 140 corpses were found in a nearby field; some of the victims had been killed in the air raid, while others had been murdered. One prisoner testified that "The SS men joked and laughed during the shooting ... the prisoners were led in groups of 15–20, they had to lie on the ground and were shot in the nape".[87] The survivors were divided into columns 100-strong and marched through heavy rain and mud. Many were ill with fever, but anyone unable to keep up was shot on the spot.[88] At Neukirchen-Balbini, the death march joined up with the larger one of non-Jewish prisoners.[89] Another group of Jewish evacuees continued towards Theresienstadt, arriving in early May.[90]

Evacuation of non-Jewish prisoners began on 17 April, when 2,000 prisoners left on foot, arriving at Dachau on 23 April. This group consisted of longtime Flossenbürg prisoners, a group from Ohrdruf concentration camp, and the survivors of the death march from Buchenwald.[84] SS official Kurt Becher, who was involved in negotiations between Himmler and the Allies, visited Flossenbürg on 17 April and attempted to persuade Koegel not to evacuate the camp.[91] A telegram from Himmler the next day repeated the order not to let any prisoner fall into enemy hands.[91][74] On 19 April, some 25,000 to 30,000 remaining prisoners in Flossenbürg and its subcamps were ordered to evacuate to Dachau.[91] About 16,000 prisoners actually set out, and only a few thousand reached their destination.[92] The prisoners were transported by rail to Oberviechtach, where they split into two groups. One of these traveled by foot and in trucks via Külz, Dieterskirchen, and Schwarzhofen, joining the earlier march of Jewish prisoners in Neunburg. Many prisoners remained in the town from 20–22 April, when the SS guards deserted. The United States Army arrived in the area on 23 April and found 2,500 surviving prisoners. Many others were liberated on the road to Cham, 34 kilometres (20 mi) to the southeast.[86]

At many of Flossenbürg's subcamps, the SS massacred sick Jewish prisoners before evacuating. Including these massacres, the death marches cost the lives of about 7,000 prisoners from Flossenbürg and its subcamps.[92] The 90th Infantry Division[93] of the United States Army liberated the main camp on 23 April and found 1,527 ill and weak prisoners in the camp hospital;[36][91] more than 100 prisoners had died in the preceding three days. Despite the efforts of American medics, only 1,208 prisoners survived the immediate aftermath of liberation. Initially, the American authorities ordered the bodies to be burned in the camp crematorium, but after protests from the survivors, held a funeral for 21 former prisoners on 3 May.[64] Some of Flossenbürg's eastern subcamps, located east of the demarcation line, were liberated by the Red Army.[94]

- Liberation of Flossenbürg

-

Former prisoners welcome the United States Army.

-

Survivors suffering from typhus

-

German civilians remove corpses from the main camp.

-

Funeral for prisoners who died after liberation

Flossenbürg Trial

[edit]

Investigation of Nazi war criminals at Flossenbürg began on 6 May 1945, when the United States Army appointed eleven investigators.[95] SS- Hauptsturmführer Friedrich Becker, the head of the labor department at Flossenbürg, had signed most of the transport lists and was considered the most important perpetrator by the American prosecutors;[36][41] Koegel had committed suicide by hanging shortly after being captured by the Americans in 1946.[36] After a year of pretrial investigation,[96] the United States charged Becker and fifty other defendants[97] on 14 May 1946.[96] The defendants, who were tried before a United States military court at Dachau between 12 June 1946 and 22 January 1947, all pleaded not guilty.[98] Thirty-three of the defendants were low-ranking SS members, sixteen were former prisoner functionaries, and two were civilians.[97] Charges against seven were dropped and five were found not guilty. Of the remainder of the defendants, fifteen received death sentences, eleven life sentences, and the remainder jail terms of varying length.[99]

After the trial, two of the prosecution witnesses were tried for perjury following a petition by the nephew of a defendant.[100] One was convicted and the other acquitted, leading to judicial review of the charges against the defendants, but a War Crimes Board of Review found that the perjury had not affected the outcome of the trial.[101] Two of the defendants who had received death sentences had their sentences reduced on appeal. The remaining death sentences were carried out on 3 and 15 October 1947 or 1948.[102] Between December 1950 and December 1951, the remaining twenty-six prisoners had their sentences reviewed. Most were commuted to time served or a shorter term. The last prisoner was paroled in 1957 and had his sentence remitted on 11 June 1958.[103]

Commemoration

[edit]

After liberation, Flossenbürg was used to hold Axis Disarmed Enemy Forces[104] and later as a displaced persons camp.[105] During the following decades, much of the camp was built over or repurposed.[106][107] For example, the former prisoner laundry and kitchen were used commercially until the 1990s.[108] The Flossenbürg camp quarry is on land owned by the Bavarian state government but is currently leased to a private company. The lease expires in 2024, and the Green Party is attempting to prevent the lease from being renewed so that the quarry can be incorporated into the memorial.[109]

The first memorial on the site was set up in 1946, and the cemetery was added during the 1950s. A small exhibition was opened in 1985, and a permanent museum opened in what had been the laundry room in 2007. A second exhibition has existed since 2010 in the prisoner kitchen.[106] A list of the names of more than 21,000 prisoners who died at the camp is available on the museum's website.[110]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The asocial category was for people who did not "fit into the mythical national community", in the words of historian Nikolaus Wachsmann.[1] Nazi raids targeted homeless people and the mentally ill, as well as the unemployed.[2]

- ^ According to SS chief Heinrich Himmler, the "criminal" prisoners at concentration camps needed to be isolated from society because they had committed offenses of a sexual or violent nature. In fact, most of the criminal prisoners were working-class men who had resorted to petty theft to support their families.[3]

- ^ Any man suspected of "lewd and lascivious" behavior with another man could be arrested and sent to a concentration camp under Paragraph 175; see persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany.[22]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 252.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 250.

- ^ a b c d e Huebner 2009, p. 560.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, pp. 1, 12.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 179, 292.

- ^ a b c Jaskot 2002, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Huebner 2009, p. 561.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2015, p. 292.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, p. 11.

- ^ KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg, Before 1938: Flossenbürg — Site of Granite.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, p. 25.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2015, p. 293.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 182.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, p. 13.

- ^ KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg, 1938: The Founding of the Flossenbürg Camp.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 294.

- ^ USHMM 2019.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 296.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2015, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Jaskot 2002, p. 38.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 297.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 346.

- ^ Huebner 2009, pp. 560–561.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f Jaskot 2002, p. 40.

- ^ a b Skriebeleit 2007, p. 27.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 504.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 497, 504.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Huebner 2009, p. 563.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 809.

- ^ Blatman 2011, p. 31.

- ^ a b Fritz 2009, p. 567.

- ^ a b c Uziel 2011, p. 182.

- ^ a b c Fritz 2009, p. 568.

- ^ Fritz 2009, p. 569.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 296, 373.

- ^ a b Jaskot 2002, p. 35.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, pp. 27, 30.

- ^ a b Jaskot 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Huebner 2009, pp. 561–562.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, pp. 28, 41, 75.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 373–374.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, pp. 41, 69, 75.

- ^ a b Jaskot 2002, p. 41.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b c Huebner 2009, p. 562.

- ^ a b Jaskot 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, p. 32.

- ^ a b Uziel 2011, p. 180.

- ^ Uziel 2011, pp. 56, 180.

- ^ Uziel 2011, p. 222.

- ^ Uziel 2011, p. 185.

- ^ Jaskot 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Huebner 2009, pp. 562–563.

- ^ a b c d Skriebeleit 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Huebner 2009, p. 564.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, p. 24.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 476–477.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 440.

- ^ Blatman 2011, p. 49.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 755–756.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 847.

- ^ a b Blatman 2011, p. 131.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2015, p. 1007.

- ^ KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg, 1941 and After: Executions and Mass Murder.

- ^ a b c d e Blatman 2011, p. 172.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 969.

- ^ Blatman 2011, p. 97.

- ^ Blatman 2011, p. 99.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Blatman 2011, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Blatman 2011, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Blatman 2011, p. 154.

- ^ a b Blatman 2011, p. 173.

- ^ Blatman 2011, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Mauriello 2017, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Blatman 2011, p. 175.

- ^ Blatman 2011, p. 176.

- ^ Mauriello 2017, p. 87.

- ^ Blatman 2011, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d Blatman 2011, p. 174.

- ^ a b Blatman 2011, p. 178.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, p. 49.

- ^ Uziel 2011, p. 234.

- ^ Riedel 2006, p. 586.

- ^ a b Riedel 2006, p. 587.

- ^ a b Riedel 2006, p. 583.

- ^ Riedel 2006, pp. 585, 588.

- ^ Riedel 2006, p. 588.

- ^ Riedel 2006, p. 595.

- ^ Riedel 2006, p. 596.

- ^ Riedel 2006, p. 597.

- ^ Riedel 2006, p. 598.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 1100.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 1103.

- ^ a b KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg, A European Place of Remembrance.

- ^ Skriebeleit 2007, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 1106.

- ^ Muggenthaler 2018.

- ^ KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg, Book of the Dead.

Sources

[edit]- Print sources

- Blatman, Daniel (2011). The Death Marches. Harvard: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05919-1.

- Fritz, Ulrich (2009). "Flossenbürg Subcamp System". In Megargee, Geoffrey P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 1. Translated by Pallavicini, Stephen. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 567–569. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- Huebner, Todd (2009). "Flossenbürg Main Camp". In Megargee, Geoffrey P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 1. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 560–565. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- Jaskot, Paul B. (2002). The Architecture of Oppression: The SS, Forced Labor and the Nazi Monumental Building Economy. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-59461-0.

- Mauriello, Christopher E. (2017). Forced Confrontation: The Politics of Dead Bodies in Germany at the End of World War II. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-4806-9.

- Riedel, Durwood (2006). "The U.S. War Crimes Tribunals at the Former Dachau Concentration Camp: Lessons for Today". Berkeley Journal of International Law. 24 (2): 554–609. doi:10.15779/Z38FD1G.

- Skriebeleit, Jörg (2007). "Flossenbürg Hauptlager" [Flossenbürg Main Camp]. In Benz, Wolfgang; Distel, Barbara (eds.). Flossenbürg: das Konzentrationslager Flossenbürg und seine Außenlager [Flossenbürg: Flossenbürg Concentration Camp and its Subcamps] (in German). Munich: C. H. Beck. pp. 11–60. ISBN 978-3-406-56229-7.

- Uziel, Daniel (2011). Arming the Luftwaffe: The German Aviation Industry in World War II. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8879-7.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2015). KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-374-11825-9.

- Web sources

- "History". KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Muggenthaler, Thomas (12 July 2018). "Antwort auf Grünen-Anfrage: KZ-Steinbruch Flossenbürg könnte weiter verpachtet werden". Bayerischer Rundfunk (in German). Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- "Persecution of Homosexuals". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Fritz, Ulrich (2009b). Flossenbürg Concentration Camp 1938–1945: Catalogue of the Permanent Exhibition. Göttingen: Wallstein. ISBN 978-3-8353-0584-7.

- Heigl, Peter; Omont, Bénédicte (1989). Konzentrationslager Flossenbürg in Geschichte und Gegenwart [Flossenbürg concentration camp in history and memory] (in German). Regensburg: Mittelbayerische Druckerei- und Verlags-Gesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-921114-29-2.

- Saalmann, Timo (2022). "Kaddish in Flossenbürg. On the Genesis of the Memorials to Jewish Victims of the Concentration Camp". Jewish Life and Culture in Germany after 1945. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. pp. 211–226. doi:10.1515/9783110750812-014. ISBN 978-3-11-075081-2.

- Siegert, Toni (1979). "Das Konzentrationslager Flossenbürg: Gegründet für sogenannte Asoziale und Kriminelle" [Flossenbürg concentration camp: Founded for so-called anti-socials and criminals]. In Broszat, Martin; Fröhlich, Elke; Wiesemann, Falk (eds.). Bayern in der NS-Zeit [Bavaria in the Nazi State] (in German). Vol. 2. Munich: Oldenbourg. pp. 429–493. ISBN 9783486483611.

External links

[edit] Media related to Flossenbürg concentration camp at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Flossenbürg concentration camp at Wikimedia Commons